Now my Master moves forward along a narrow path

between the torments and the city wall,

and I follow close behind him.

"O supreme power, who leads me as you will

through these circles of the damned," I began,

"speak to me and satisfy my longing—

The people lying in these tombs,

can they be seen? All the lids

are raised, and no one stands guard."

And he replied: "They will all be sealed shut

when they return from the valley of Jehoshaphat

with the bodies they left behind above.

On this side lies their cemetery,

with Epicurus and all his followers

who believe the soul dies with the body.

But the question you ask me now

will soon be answered here within,

along with the wish you keep silent."

And I said: "Good Leader, I only hide

my heart from you so I might speak less,

and this isn't the first time you've encouraged me to this."

"O Tuscan, you who pass alive

through this city of fire,

speaking so courteously,

please stop your steps in this place.

Your way of speaking reveals you

as native to that noble homeland

to which perhaps I brought too much harm."

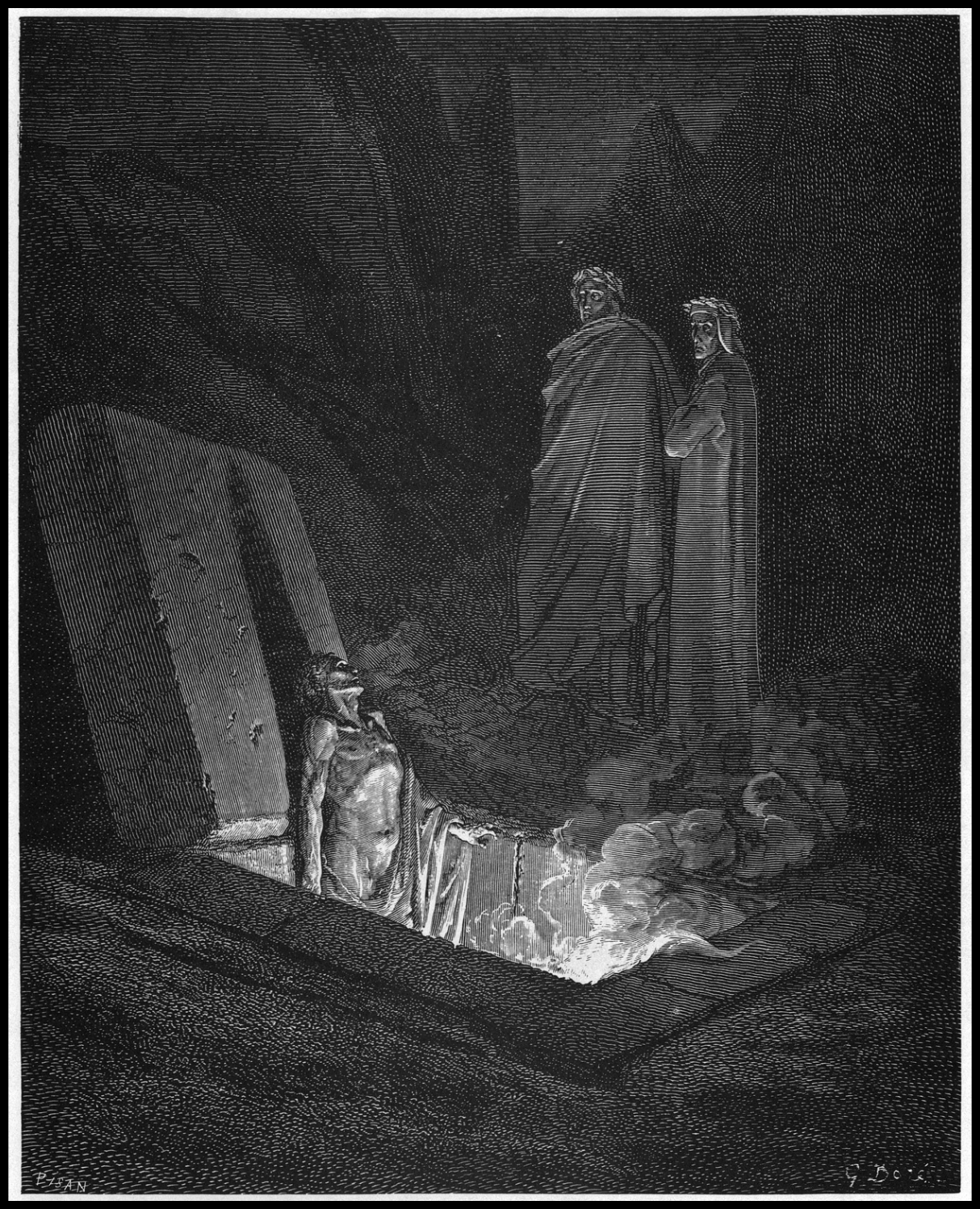

Suddenly this voice burst forth

from one of the tombs, and I pressed closer

to my Leader in fear.

He said to me: "Turn around—what are you doing?

Look, there's Farinata rising up;

you'll see him completely

from the waist up."

I had already fixed my eyes on his,

and he rose upright with chest and brow

as if he held Hell itself

in utter contempt.

My Leader's bold and ready hands

pushed me toward him between the sepulchers,

saying, "Let your words be clear."

View larger

FARINATA

“My Leader's bold and ready hands / pushed me toward him between the sepulchers, / saying, "Let your words be clear."”

When I reached the foot of his tomb,

he studied me for a moment, then,

as if disdainful, asked: "Who were your ancestors?"

Eager to obey, I concealed nothing

but revealed everything to him.

At this he raised his eyebrows slightly.

Then he said: "They were fierce enemies

to me, my fathers, and my party,

so I scattered them twice."

"If they were exiled, they returned both times

from every direction," I answered him,

"but your people never mastered that skill."

Then another shadow appeared beside him,

visible down to his chin—

I think he had risen to his knees.

He looked around me as if anxious

to see whether someone else was with me,

but when his doubt was satisfied,

weeping, he said: "If you pass through this blind

prison by virtue of your high genius,

where is my son? Why isn't he with you?"

And I replied: "I don't come by my own power.

He who waits over there leads me here—

the one your Guido perhaps held in scorn."

His words and the nature of his punishment

had already told me his name,

which is why my answer was so complete.

Suddenly starting up, he cried: "What

did you say—he held? Isn't he still alive?

Doesn't the sweet light still strike his eyes?"

When he noticed the delay

I made before answering, he fell

backward and appeared no more.

But the other, that great soul at whose request

I had stopped, didn't change expression—

he neither moved his neck nor bent his body.

"And if," continuing our first conversation,

"they haven't learned that skill well," he said,

"that torments me more than this bed.

But the face of the Queen who reigns here

won't be rekindled fifty times

before you'll know how hard that skill is.

And so you may return to the sweet world,

tell me: why is that people so merciless

against my family in all their laws?"

I answered him: "The slaughter and great carnage

that stained the Arbia red with blood—

that's why such prayers are made in our temple."

Shaking his head with a sigh, he said:

"I wasn't alone there, and surely

I didn't move with the others without cause.

But I was alone where everyone else

agreed to destroy Florence—

I alone defended her openly."

"Ah, so your descendants may find peace,"

I begged him, "untie this knot for me

that has tangled my understanding here.

It seems, if I hear correctly,

that you can see what time will bring,

but with the present it's different."

"We see like those with poor sight,"

he said, "things that are distant from us—

so much light the Supreme Ruler still gives us.

When they draw near or are present,

our understanding fails completely,

and unless someone brings us news,

we know nothing of your human condition.

So you can understand that our knowledge

will die completely when

the door to the future is closed."

Then I, as if sorry for my error,

said: "Now tell that fallen one

that his son is still joined with the living,

and if I was silent before in answering,

tell him it was because I was already thinking

about the confusion you've now resolved for me."

My Master was already calling me back,

so I begged the spirit more urgently

to tell me who was there with him.

He said: "I lie here with more than a thousand.

Inside here is the second Frederick

and the Cardinal—I won't speak of the others."

Then he hid himself, and I turned

toward the ancient poet, pondering

those words that seemed ominous to me.

He began walking, and as we went,

he said: "Why are you so troubled?"

I satisfied his question,

and that wise one commanded me:

"Keep in memory what you've heard against yourself,

and now listen carefully"—he raised his finger—

"when you stand before the sweet radiance

of her whose beautiful eyes see everything,

from her you'll learn your life's journey."

Then he turned his steps to the left.

We left the wall and headed toward the center

along a path that leads down to a valley

whose stench, even from up there,

was foul and overwhelming.