The sudden panic had scattered the souls across the plain,

all fleeing toward the mountain where reason calls us.

I pressed close to my faithful guide—

without him, how could I have found my way?

Who else would lead me up this sacred slope?

He seemed lost in self-reproach,

this noble conscience, pure and unstained—

how sharply even the smallest fault can wound

a spirit so refined!

Once he shed the haste

that robs all action of its dignity,

my mind, which had been focused tight with fear,

released itself like something set free to wander.

I lifted my gaze toward the hill

that reaches highest toward heaven.

The sun, blazing red behind us,

shattered into fragments before me

where my body blocked its rays.

I turned aside in terror

of being abandoned, when I saw

only darkness stretching ahead of me.

"Why do you still doubt?" my comforter said,

turning to face me fully.

"Don't you believe I'm with you? That I guide you?

Where my body lies buried, evening has already fallen—

taken from Brindisi, now resting in Naples.

If I cast no shadow before me,

don't marvel at this any more

than you wonder at the heavens,

where one ray doesn't prevent another

from passing through.

Bodies like mine, designed

to suffer both burning cold and searing heat—

this Power provides them, willing

that how it works remain hidden from us.

Mad is the one who hopes our reason

can traverse that infinite path

which One Substance in Three Persons follows.

You mortals must be content with knowing that it is—

for if you could have seen everything,

Mary would not have needed to give birth.

You've watched the fruitless longing

of those whose desire should have been fulfilled,

but which instead becomes their eternal grief.

I speak of Aristotle and Plato,

and many others—"

Here he bowed his head,

said nothing more, and stayed troubled.

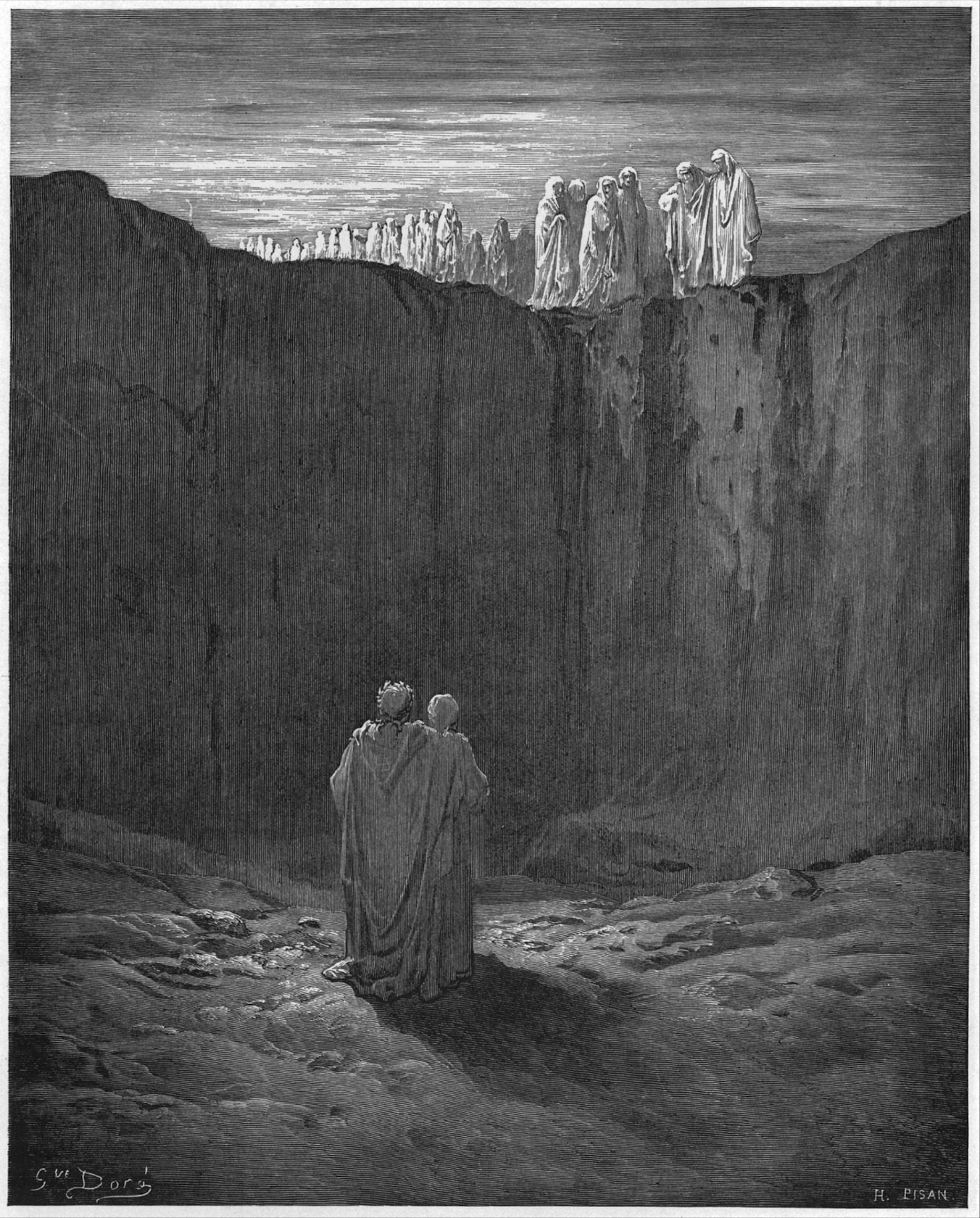

We reached the mountain's base at last,

where we found the rock face so sheer

that even the most agile legs would fail.

Between Lerici and Turbia, the most desolate,

most isolated path would seem

an easy, open stair compared to this.

"Who can tell which way the slope

curves down," my master said, stopping,

"so that someone without wings might climb?"

While he studied the ground,

examining the nature of our path,

and I gazed up at the towering rock,

I noticed on our left

a crowd of souls moving toward us—

though they came so slowly

they seemed not to move at all.

View larger

THE MOUNTAIN'S FOOT

“While he studied the ground, / examining the nature of our path, / and I gazed up at the towering rock,”

"Look up," I said to my guide.

"See there—they might give us counsel

if you can't find it on your own."

He turned to me with open expression:

"Let's go to them, since they approach so slowly.

And you, sweet son, stay firm in hope."

That group was still as far from us,

after we'd taken a thousand steps,

as a strong arm could throw a stone,

when they all pressed against

the hard masses of the high cliff,

standing motionless and tight together,

like someone stopping to stare in doubt.

"O blessed dead! O souls already chosen!"

Virgil began. "By that peace

which I believe awaits you all,

tell us which way the mountain slopes

so we can find a path up.

Time lost most troubles those who know its worth."

Like sheep emerging from their fold

in ones and twos and threes,

while the others stand timid,

eyes and noses to the ground—

and whatever the first one does, the others copy,

huddling against her if she stops,

simple and quiet, not knowing why—

so I saw the leader of that blessed flock

begin to move toward us,

modest in face, dignified in bearing.

When those in front saw the light

broken on the ground at my right side,

the shadow stretching from me to the rock,

they stopped and drew back somewhat.

All the others following behind,

not knowing why, did the same.

"Without your asking, I confess to you—

this is a human body you see here,

which cuts the sunlight on the ground.

Don't marvel at this, but trust

that only through a power sent from heaven

does he attempt to climb this wall."

So spoke my master. Those worthy souls replied:

"Turn back then, and go before us,"

gesturing with the backs of their hands.

One of them began: "Whoever you are,

walking this way, turn and look—

consider if you ever saw me in the other world."

I turned toward him and studied him closely.

He was blond, beautiful, noble in appearance,

but a blow had split one of his eyebrows.

When I humbly denied

ever having seen him, he said, "Look now!"

and showed me a wound high on his chest.

Then, smiling: "I am Manfred,

grandson of Empress Constance.

So when you return, I beg you—

go to my beautiful daughter,

mother of Sicily's honor and Aragon's,

and tell her the truth, if other tales are told.

After my body was torn

by these two mortal wounds,

weeping, I gave myself to Him

who gladly pardons.

My sins were horrible,

but Infinite Goodness has arms so wide

they embrace whatever turns to them.

If only Cosenza's bishop,

sent by Clement to hunt me down,

had read this page of God's nature right—

the bones of my dead body would still lie

at the bridge near Benevento,

protected by that heavy pile of stones.

Now rain washes them and wind scatters them

outside the kingdom, almost by the Verde River,

where he moved them with extinguished candles.

Their curse cannot destroy Eternal Love

so completely that it cannot return,

as long as hope shows any green.

True—whoever dies in defiance

of Holy Church, though repentant at the end,

must wait outside this bank

thirty times the span they spent

in their presumption,

unless righteous prayers shorten the decree.

See now if you have power to make me happy

by telling my good Constance

that you've seen me, and about this ban—

for those on earth can help us greatly here."